This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

A reflection of Social Forestry in 2019: Towards inclusive and collaborative government approaches

Corresponding Author(s) : Didik Suharjito

Forest and Society,

Vol. 3 No. 1 (2019): APRIL

Abstract

Keywords

Full text article

1. The national level: The main bureaucratic driver (MOEF) partnering with civil society

In this article, we present a reflection on direct observations in various forums, including those convened by the government and by civil society groups. One of them was conducted at the national level, including a reflection session by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (MOEF) in partnership with Tempo Magazine. This reflection was presented directly through Tempo’s social media networks and uploaded to youtube. The reflection discussion was also attended by the MOEF minister and several MOEF director generals, as well as other national NGOs actively engaged in social forestry, farmer group representatives from social forestry sites, and other national media. The event sought to conduct a reflection on the progress of social forestry at the end of 2018, both in terms of policy application and implementation in Indonesia, which is now becoming more popularly known as “hutansosial” or as the contraction “hutsos.” During the session, one of the key areas that stood out about the past four years of hutsos is government’s continued commitment to being more inclusive and collaborative.

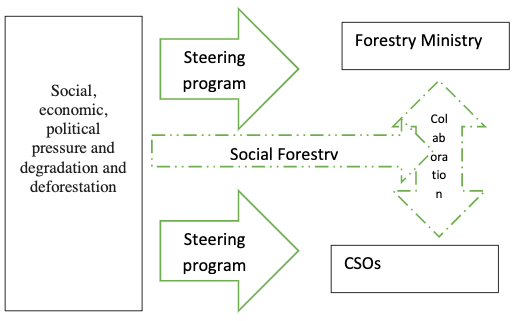

The following are three key areas that were identified by the forum to have undergone considerable change in the past twenty years regarding the role of government more broadly: (1) The government as the dominant (and only) actor in creating, promoting, and implementing policy, (2) The government involving CSOs (a broad category of actors and institutions that include non-government organizations, non-private, and corporate) to implement activities or programs for community empowerment (a broad category of various terms and concepts of social welfare programs) separately from the formal government programs, (3) The government receiving input and recommendations from CSOs (both solicited and unsolicited), (4) The government actively invites participation among local communities, and (5) The government actively collaborates with CSOs, including in the past two or three years implementing the “collaborative-plus” model.

From a CSO perspective, roles have also undergone changes from the first-, to the second-, third-, and fourth-generation (borrowing from a terminology coined by David Korten, 1990), and is now entering a shift to a phase of fourth-generation-plus. The room for engagement among CSOs today is not only limited to direct service agreements at the community level in terms of poverty alleviation, increasing community capacity, policy advocacy, and facilitating networks, but have expanded further beyond these elements. Furthermore, CSO movements today are no longer viewed as negative by the government.

Figure 1. Shifting relations between Government and CSOs in Social Forestry

The fact that government has become more inclusive is evident from their recognition of the possibilities for communities to reside in and around forest boundaries (that were in the past viewed as a disturbance and illegal actors) and furthermore, the formal view that indigenous (adat) communities can serve as the main actors or key partners in forest management. In this way, government is no longer only engaging with large corporations, but also serving local and indigenous communities by providing legal access and supporting local livelihoods. The overall view about the role of government has also become much broader. However, these principles of inclusivity must be further supported by various mechanisms and systems for serving communities in more accessible ways, especially for the most vulnerable, albeit the government now claiming to have applied the principle of "jemput bola," or making the first step in going to the communities to engage with them.

Government collaboration with CSOs was not only initially conducted in the aims of jointly formulating policy, but rather was created in order to develop working relationships at the national and regional levels. We have not yet seen a clear indication of how this working relationship will take shape, whether for example, the mission and vision and the overall objectives will be drafted jointly, such that budget-sharing, activity implementation, monitoring and evaluation, and the overall successes and failures will be borne together.

Inclusivity and collaboration-plus, between government and CSOs is the main factor for the increasing rate of social forestry designations, as well as the associated increase in the number of groups, overall territorial expansion areas, and types of services (including trainings and small business investments through social forestry). Collaboration-plus has not been limited to partnerships with CSOs, but furthermore has also taken place across other ministries and government agencies at different levels. Through social forestry it has been proved that something difficult to achieve has indeed been possible, albeit still limited to those directly involved and the specific types of engagement. One area that is still surprisingly weak are the collaborations taking place internally across MOEF divisions. As a result, there is a clear indication that social forestry has not become internalized as part of the broader mission/vision of all working units at MOEF.

On the other hand, the reflection session at the national level forum also highlighted the numerous problems internally at MOEF, which are still an area of disagreement among internal leadership at the ministry. Working relationship remain piecemeal between different MOEF sectors that are still being addressed on a case-by-case basis, and not addressed systematically. Indeed, one CSO representative in attendance highlighted that the crisis on the legal differences of opinion and applications of social forestry within the ministry cannot be fully addressed internally, but requires the intervention of the president due to the contentious legal complexity of the issue (see Sahide and Giessen, 2015).

2. Relations with regional governing: Reflections in Lampung and South Sulawesi

Aside from these intriguing developments at the national level, we also sought to engage on the applications of social forestry across governing scales. We attended three events reflecting on social forestry at the end of 2018 in the provinces of Lampung and South Sulawesi. The first reflection session in Lampung was convened by WALHI Lampung, an environmental NGO. The second involved a meeting on the development of social forestry convened by the Forestry Agency and the Lampung Provincial Working Team on the Acceleration of Development in the Agricultural, Fisheries, and Forestry Sectors (TP4K). The third, involved a joint discussion of stakeholders on the impacts of social forestry in South Sulawesi that was hosted by the Forestry Faculty at Hasanuddin University in partnership with the Social Forestry and Environmental Partnership Agency of the Sulawesi Region at MOEF.

One of the overarching points that emerged across the three meetings relates to the overall meaning of “Working Groups” (Pokja) on the Acceleration of Social Forestry Implementation. Findings highlighted that these working groups have not yet been able to successfully support the acceleration process because it is not only the achievement of area designation that is desired. The overall desired objectives include the continued facilitation post- permit designation, including support for marketing functions, developing production systems of non-timber forest products, eco-tourism development support, continued empowerment of farmer groups based on their existing capacity, increasing activities by forestry extension officers, and other human resources support from the Forest Management Units (KPH). There was also a desire among attendees that there be a standard of mutual understanding between community members, the government, and facilitating NGOs about their overall responsibilities among their roles in accelerating the designation of social forestry. This was particularly true for the partnership (kemitraan) scheme. This is reasonable due to the fact that Indonesia has a complex mechanism for the partnership scheme, which is divided by protection, production and conservation forest. Overall, the coordination and working relationship between the district government and local NGOs were considered of great importance, but which had not received much attention. This is especially true when seen from the perspective of district governments that can help to play a strategic role in the continued sustainability of social forestry by providing support through local budgets (APBD) and the engagement of designated OPDs (Regional Service Organizations). Furthermore, local NGOs can more easily facilitate support with local communities and better understand local context, and are more easily able to address local shortcomings, while also being able to help support assigned social forestry facilitators and extension workers.

Then there is the issue of Article 61 paragraph 4 of the Ministerial Regulation No. P.83 of 2016, which mandates the rehabilitation of land and conservation of forest and water resources. In 2019, the Lampung province received budget allocation for a rehabilitation program through the Watershed Management Agency of MOEF, but it turns out they were not permitted to conduct any activities at social forestry locations due to the existing designation at these locations. In practice however, it would have been possible to further incentivize communities with social forestry permits to achieve mutual goals.

Furthermore, there were also discussions about the need for better coordination in the coming years between the forestry agencies in the region and other sectoral agencies, as well as engaging in more effective working relationships with the private sector and NGOs. This coordination is essential because realities in the field highlight numerous overlapping programs. The discussion between the Forestry Agency and TP4K also included various recommendations by the TP4K team, including: (1) Lampung should develop social forestry pilot sites that can showcase positive implementation at each KPH location, (2) Monitoring and evaluation guidelines for social forestry that meet field conditions, and (3) The development of a regional regulation (PERDA) on Sustainable Forest Management that includes social forestry considerations.

Specific to the South Sulawesi discussion, the social impact assessment (Sahide et al., 2018) found that facilitation determines the key outcomes of social forestry success. Evaluating the overall impact of social forestry should not only be measured by its financial outcomes, but that there should also be consideration given to the overall impacts of economic development of a region, especially in areas that have implemented social forestry effectively. It was also found that planning documents in South Sulawesi needed to be better targeted and tailored to the local context, both in terms of local literacy and more representative local knowledge. In this light, it was found that various social forestry locations had developed successful agroforestry cultivation programs without the formal planning documents, or in other cases, planning documents did not reflect local land management systems. Requirements for forest management planning documents should be more closely reviewed so that they can be simplified in ways that support local contexts because they do not directly correlate with the existing local wisdom of forest planning at the village level.

In sum, social forestry in Indonesia has brought together a complex interaction between MOEF and civil Society actors. At the outset, civil society organizations focused more on advocacy about the rights of rural communities to national forests. However, recent policy developments highlight a shift in their roles to one that is much more engaged in the active participation and facilitation in order to support inclusive approaches.

Download Citation

Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)BibTeX

- Korten, D. C. (1990). Getting to the 21st century: Voluntary action and the global agenda. Kumarian Press

- Sahide, M.A.K, Jusuf, Y., Alam, S., Supratman., Millang, S., Mahbub, A.S., Bachtiar, B., Sabar, A., Nasri., Nursaputra, A., Ahmad, M.F., Yahya, N.H. (2018). Kajian Dampak Perhutanan Sosial di Provinsi Sulawesi Selatan. Fakultas Kehutanan Universitas Hasanuddin dan Balai Perhutanan Sosial dan Kemitraan Lingkungan Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan, Makassar, Indonesia.

- Sahide, M. A. K., & Giessen, L. (2015). The fragmented land use administration in Indonesia–Analysing bureaucratic responsibilities influencing tropical rainforest transformation systems. Land Use Policy, 43, 96-110. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.11.005

References

Korten, D. C. (1990). Getting to the 21st century: Voluntary action and the global agenda. Kumarian Press

Sahide, M.A.K, Jusuf, Y., Alam, S., Supratman., Millang, S., Mahbub, A.S., Bachtiar, B., Sabar, A., Nasri., Nursaputra, A., Ahmad, M.F., Yahya, N.H. (2018). Kajian Dampak Perhutanan Sosial di Provinsi Sulawesi Selatan. Fakultas Kehutanan Universitas Hasanuddin dan Balai Perhutanan Sosial dan Kemitraan Lingkungan Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan, Makassar, Indonesia.

Sahide, M. A. K., & Giessen, L. (2015). The fragmented land use administration in Indonesia–Analysing bureaucratic responsibilities influencing tropical rainforest transformation systems. Land Use Policy, 43, 96-110. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.11.005