This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Community preferences for social forestry facilitation programming in Lampung, Indonesia

Corresponding Author(s) : Christine Wulandari

Forest and Society,

Vol. 3 No. 1 (2019): APRIL

Abstract

Keywords

Full text article

1. Introduction

Studies have devoted great attention to the provision of support for communities on the sustainability of Social Forestry (SF) programs (Gupta and Koontz, 2019; Duguma et al., 2018; Barsimantov, 2010). Among these studies, the government, NGOs, private sector, and other external actors support communities in various forms. For example, extension agencies have supported communities in the technical aspects of cultivation, processing, and marketing of acacia plantations in Kalimantan, Indonesia (Nawir, 2011). An Indian case also highlights private sector support for communities to build their technical capacity in managing forest land so that communities can improve their livelihoods (Dongre, 2011). Beyond the technical activities however, facilitation for SF also includes support for policy development of SF programs as described in a case from Sweden (Mårald et al., 2015) and Indonesia (Kurniasih, 2016). The provision of support for communities in Indonesian SF programs is defined in the regulations as pendampingan (facilitation). Facilitation is also a common term used by communities, NGOs, government officials and other actors in Indonesia. In this paper, facilitation is loosely defined to include the provision of support for communities in various forms such as training programs for capacity building on technical forest management activities, provision of marketing information, policy development of SF programs and also a transfer of knowledge to communities.

Research suggests that facilitation empowers communities and builds community capacities (Barsimantov, 2010). McDougall et al. (2009) underline that facilitating learning could enhance ‘an adaptive collaborative approach' in community forest user groups. Facilitation by researchers, policymakers, and other actors could improve the sharing of scientific knowledge to complement the existing knowledge of local communities (Mvondo and Oyono, 2004). A recent study by Wulandari and Inoue (2018) found that in villages where a number of diverse types of facilitation are taking place, communities more actively participate in SF programs. The forest user groups in the study area had a high commitment to collaborate with facilitators from governments, NGOs and universities (Wulandari and Inoue, 2018). In Indonesia, the recent expansion of SF programs incorporate government commitments to facilitate communities with an expectation that it could lead to improved SF outcomes. In several regulations, for example, Forestry Minister Regulations No. 83/2016 on SF, among others, in which facilitation is legally recognized as a mechanism to leverage SF. Minister of Forestry Regulation 29/2013 and 57/2014 also requires facilitation for community forest user groups to increase productivity, to solve problems, and to improve the welfare of communities associated with SF programs. These can also be conducted through extension services provided by external stakeholders such as government and NGOs (Minister of Forestry Regulation 57/2014).

The complexities in SF and the diverse roles of actors in SF means there is not one approach of facilitation fits all conditions. One undesirable outcome from the results of external facilitation are the continuous dependencies of local communities to external support, as found in cases of certified teak growers in Lao PDR (Ling et al., 2018). To avoid this outcome, external stakeholders from the government, research organizations, and donor agencies have produced some guidelines for facilitating SF through governance or technical support activities (e.g. in McDougall et al., 2009). Some studies have also identified what kind of specific types of facilitation are required (e.g. Gupta and Koontz, 2019). However, there is still a need to understand which types of stakeholders should be facilitated and how facilitation should be done to ensure the sustainability of SF programs.

The experience of SF in Indonesia for almost three decades now shows that community forest user groups (FUGs) are established at different points of times. However, the existing studies on facilitation for SF in Indonesia have mainly focused on the types of facilitation, without linking them with the duration of establishment of the community organizations. Meanwhile, the needs and the capacities of community groups may change over time across diverse socio-economic contexts (Sapkota et al. 2018). The training on capacity building projects often reinvent the wheel along with cycles that follow programs by donor agencies, NGOs or other support actors do not take a longer view of FUGs into account, often overlooking the existing capacities that have been developed with communities over time.

Given this background, this paper attempts to fill in the gap by discussing facilitation for communities involved in Indonesian SF by examining cases of SF in Lampung. The paper thus focuses the analysis on answering two main questions:

- Which stakeholders should be prioritized to receive facilitation?

- What type of facilitation is required among various community groups that were established at different periods?

2. Materials and Methods

This paper is based on the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), an analytical approach based on of empirical data collected from field research between May to October 2017 in Pekon Tri Budisukur, Lampung Barat district, Lampung province (see Figure 1). The Pekon Tri Budisukur was one of the ten villages in Lampung Barat district to receive community forestry designation (Hutan Kemasyarakatan, or henceforth, HKm). It is one of the earliest formal SF programs in Indonesia, and began implementation more than twenty years ago. In this village, two community FUGs i.e. Bina Wana HKm group and Melati women farmer group were established in 1998 and 1993. Through the HKm scheme, the FUGs were granted a right to manage and utilize nontimber forest products in 538 ha of lands within a protected forest. The HKm program and the FUGs in this location are chosen for this study because of the duration of the HKm program and the overall community involvement in SF programming for close to thirty years. The research questions posited for this study require information obtained from research participants who have first-hand experiences and understanding about types of facilitation delivered to FUGs at different periods, and information about which stakeholders were prioritized. Their long involvement in SF at this location provides rich knowledge and experiences to identify support that they have determined they needed, and they also have information about which stakeholders should be prioritized in the facilitation program.

Figure 1. Pekon Tri Budisukur, the location of field study (source: Badan Informasi Geospatial)

Qualitative and quantitative data were collected from 58 members of Bina Wana HKm Group and 63 members of Melati Women Farmer Group, which amount to a total of 121 respondents. Through the HKm SF scheme, these two groups have rights to utilize nontimber forest products such as palm sugar, durian, and honey while also taking on the responsibility for protecting areas in protected forests. The Bina Wana FUG consists of 15 sub-groups, comprising of 615 members. The Melati Women Farmer Group is a women’s FUG comprising of the wives of the FUG Bina Wana members. The key activity is processing and marketing forest products from the HKm area to the local market. The membership is voluntary, and amount to a total of 97 members.

The number of samples for this study is selected based on the Slovin Formula, taking into account the total active members of the HKm Group (111 members) and the active members of Women Farmer Group (63 members).

First, from each subgroup of the Bina Wana FUG, seven or eight active members were selected, from a total number of active members amounting to 111 members of the FUG. The selected members from the Melati FUG were 63 women who actively participated in the program. The Slovin Formula provides a sample size (n) using the known population size (N) and the desired margin of error (5 % margin of error) (e). The N and e values are incorporated into the formula:

The resulting value of n equals the sample size to be used. Slovin's Formula calculates the number of samples required when the population is too large to directly sample every member. Slovin's formula works for simple random sampling. The sample for this study is drawn using this simple method because all of the respondents are members of the HKm.

The data was collected using FGDs and questionnaires. FGDs were conducted with the HKm members who were predominately male, and for women’s FUG members who were all female. Respondents were asked to choose, according to their preference, who should receive facilitation support, what types of facilitation were needed, and the target groups of the facilitation. These were aggregated temporally, as we asked these questions relative to the types of facilitation appropriate for a newly established FUG (0-5 years), at age 6-10 years, and at an age greater than 10 years.

Data were analyzed using AHP, which is “a theory of measurement conducted through the pairwise comparisons, and which relies on the judgments of experts to derive priority scales” (Saaty 2008: 83). In this study, FUGs decided which stakeholders should be prioritized in the facilitation program and what facilitation the groups needed at different periods. AHP is used to draw a ratio scale from the various pairwise comparisons that is either discrete or continuous. The paired comparisons could then be acquired from actual measurements or relative measurements of the degree of interests (Saaty, 2008). Therefore, AHP is useful in drawing out the ratio scales of aspects that would be difficult to be measured otherwise, which in this case is related to the respondent perception about facilitation that is received or expected by the respondents. The analysis using the AHP method therefore enables a comparison of various stakeholder perspectives on the priorities of facilitation: what types of facilitation, which stakeholders should be facilitated, and the types of supports needed at different periods of group establishment.

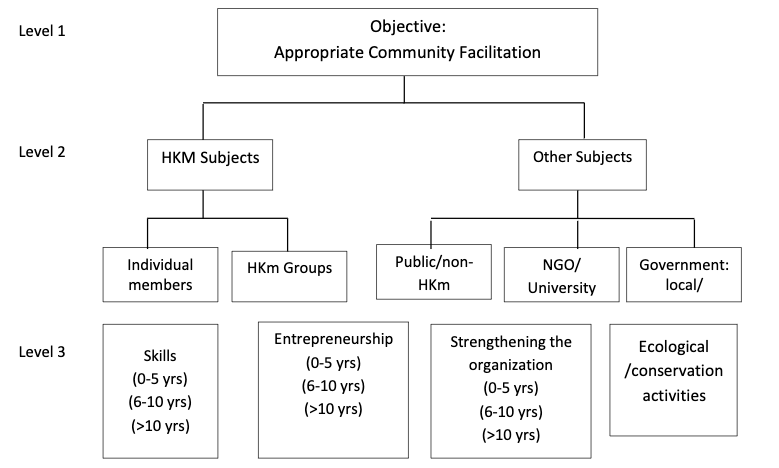

The AHP analysis began with the establishment of a hierarchical structure or networks of the research problems. The hierarchical structure comprises three levels, namely:

- Level 1 is the purpose of the research namely to developing appropriate facilitation for sustainability of HKm program in Lampung Province.

- Level 2 is the subject implementing the HKm program (the main stakeholders) and additional stakeholders which comprise individual, FUGs, and the public (villagers who are non-HKm members), NGOs and Universities, and government (district, province, and central government).

- Level 3 is the types of facilitation which are based on the categories of improving skills, entrepreneurship, strengthening institutions, and ecological conservation activities. Skills include the capacities in managing seedlings, processing non-timber forest products (e.g. honey, palm sugar) into higher value products. Entrepreneurship includes the capacities in marketing forest products into the commercial market. Strengthening institutions includes enhancing FUG skills in administrative compliance and negotiation skills to increase bargaining positions. Ecological conservation includes FUG activities relevant to forest conservation such as conserving the land from erosion using terracing method.

The age of the organization is categorized into three: (1) up to 5 years (2) 6-10 years, (3) >10 years.

The hierarchical structure is based on the aims of this research detailed in Figure 2.

The lines connecting the boxes across levels represent relations that need to be assessed using pairwise comparisons with a direction from the lower level to the higher level. Level 1 is the objective of developing an appropriate facilitation approach for community development in HKm programs in Lampung–based on the various types of facilitation at Level 3. Factors at Level 2 are assessed by using a pairwise comparison to Level 1. For example, in choosing the subjects who need facilitation, the questions related to which stakeholders should be prioritized in the facilitation, namely: HKm subjects (main stakeholders) or Other Subjects (additional stakeholders); individual members or HKm groups; HKm members and non-HKm members in the same community; etc. The factors were then assessed in relative terms to each other, using the relative measuring scale of 1 to 9 (Saaty 2008).

3. Results

This section presents the results of the AHP analysis in which a hierarchical structure was developed at three levels.

3.1. Analysis Level 2: which stakeholders should be facilitated?

Five main stakeholders related to the implementation of HKm were identified. Individuals represent distinct members while HKm group refers to the organization of the FUG. These stakeholders are directly involved in implementing HKm so that they are categorized as the main stakeholders (HKm Subjects). The Public refers to villagers who are not involved in the Hkm Groups. NGO/University refers to NGOs and University of Lampung which provide facilitation programs to communities in the village (facilitators). Government includes district, province, and national governments. These stakeholders are categorized as additional stakeholders (Other Subjects).

Table 1. Results of analysis at level 2

| Individual | HKm Group | Public | NGO/Univ | Govt | Eigen Vector | |

| Individual | 0.55556 | 0.5602241 | 0.470588 | 0.315789 | 0.344828 | 0.449396988 |

| HKm Group | 0.18333 | 0.280112 | 0.029412 | 0.210526 | 0.275862 | 0.195849106 |

| Public | 0.09444 | 0.0560224 | 0.117647 | 0.263158 | 0.275862 | 0.161426775 |

| NGO/Univ | 0.09444 | 0.047619 | 0.352941 | 0.052632 | 0.034483 | 0.116423801 |

| Govt | 0.07222 | 0.0560224 | 0.029412 | 0.157895 | 0.068966 | 0.076903330 |

Table 1 lists the results of the analysis at level two. The importance of one stakeholder to receive SF facilitation in comparison to the others is analyzed based on the comparison of Eigen vector numbers.

The result shows that respondents first prioritized facilitations for individual members than for the HKm group. The calculation of the comparison number of Eigen vector shows that the individual is 0.449396988 divided by 0.195849106 or 2.2946 times more important than the HKm group. The reason for prioritizing individual members relate to the current practices, in which external actors directly invite specific FUG members to attend training; this practice creates privilege to these invited members but hinder other members to develop capacity themselves. Meanwhile, the respondents perceive the needs for every member to have equal opportunities to attend training outside the village as a representative of the FUGs and then share the knowledge and skills obtained in the training when they return to the village. The second priority for facilitation is for the organization (i.e. HKm groups). For example, in regard to capacity building training, facilitating HKm groups could be done by involving all members of FUGs by conducting training in the village.

The third priority, according to the respondents, is facilitation to the Public (i.e villagers who are not part of HKm groups). The result shows that facilitation for HKm group is 1.213 times more important than for the villagers. The reasons for facilitating other villagers, according to the respondents, are the social connections between HKm members and other villagers. In the forest village, even though the other villagers are not directly involved in the FUG, the HKm members interact with non-members on a daily basis as their livelihoods are inseparable from other villagers. Respondents expect SF stakeholders, including villagers who are not involved in HKm, to understand the program and support HKm members in the implementation of program activities such as maintaining trees in HKm plots.

The fourth priority is facilitation for NGOs and universities. These stakeholders have priority value 1.513 times more important than the government. The position is below the non-HKm villagers which have priority value 1.384 in comparison to NGOs and universities. Respondents perceive that the facilitators from NGOs and universities need to continuously update their knowledge as well as their understanding of the characteristics of communities where they work. There is a current gap in the knowledge and skills of facilitators in technical aspects such as how to address the issue faced by HKm members who are prohibited to cut the trees in their HKm plots even though the canopy has covered the coffee plants. Respondents also expect community facilitators to understand the changes in community characteristics such as demographic changes. For example, adult children move to other places for work or marriage, while elderly group members have limitations to manage HKm areas. In the fifth position to be prioritized is the government (various agencies from district, province and national government). Respondents expect that the government could adapt existing policies to conditions that evolve at the community level. However, in the current situation, the FUG members perceive that the dynamic occurring in the field is not taken into account by the government actors who directly facilitate communities and the policymakers who make policy decisions.

3.2. Analysis Level 3: what types, and when should facilitation be provided for HKm implementers?

This section discusses the community preferences for types and timing for facilitation. Four types of facilitation for the HKm implementers include (technical) skills, entrepreneurship, strengthening organizations, and ecological or conservation activities. The ages of the groups are divided into three categories: facilitation for newly established FUG (up to five years), FUG that has been established for 6-10 years, and FUG that have been established for more than 10 years.

Table 2. Results of analysis at level 3

| A1 | A2 | A3 | B1 | B2 | B3 | C1 | C2 | C3 | D | Eigen Vector | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| A1 | 0.088 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.1 | 0.06 | 0.10224386 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| A2 | 0.177 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.06819715 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| A3 | 0.177 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.07128010 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| B1 | 0.044 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.23 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.16 | 0.13649716 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| B2 | 0.029 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.16 | 0.12285744 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| B3 | 0.177 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.31 | 0.3 | 0.23 | 0.13 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.19 | 0.21235613 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| C1 | 0.088 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.07336229 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| C2 | 0.088 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.07714761 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| C3 | 0.088 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.2 | 0.13 | 0.1 | 0.09 | 0.10641511 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| D | 0.044 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02964315 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Remarks | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A1 = Skills (groups age: up to 5 years) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A2 = Skills (6 - 10 years) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A3 = Skills ( ≥ 10 years) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| B1 = Entrepreneurship (up to 5 years) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| B2 = Entrepreneurship (6 - 10 years) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| B3 = Entrepreneurship ( ≥ 10 years) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C1= Strengthening Organization (up to 5 years) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C2= Strengthening Organization (6 - 10 years) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C3= Strengthening Organization (≥ 10 years) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| D = Ecological/ Conservation Activities | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The results show that the respondents put the highest preference for facilitation for entrepreneurship. They express that this is more important than facilitation for improving other technical skills and strengthening institutions. According to the respondents, entrepreneurship is most needed when HKm groups have been established for more than 10 years. Facilitation for entrepreneurship is also needed when a FUG is newly founded (when the group age is between 0-5 years). Lastly, entrepreneurship facilitation is less needed for FUG ages 6-10 years.

The research participants place secondary priority for facilitation to improve skills in the following aspects: post-harvest production, information technology to reach the market, and eco-tourism. The research participants have identified the changes in market interests to their forest commodities and in the changes in the distribution system for coffee, palm sugar, and other non-timber forest products. Thereafter, they would like to enhance their skills to process forest products into higher value products and to attract the buyers; to develop knowledge for web-based marketing, and skills to manage and promote the landscapes for community-based eco-tourism in the protection forest managed by the HKm groups.

The respondents place strengthening organizations as the third preference for facilitation. Facilitation to strengthening organizations includes improving administrative skills to comply with HKm program requirements and maintaining social capital of the community to address the new challenges in implementing the HKm program. Based on a previous study, one potential reason for this priority is the weakened condition of the existing social capital within the group (Wulandari and Budiono 2015).

The groups still require facilitation on ecological and conservation activities but decided that facilitation in this respect is the last priority. The need to fulfill livelihood needs and other needs (e.g. education costs) require them to balance the livelihood and ecological activities in HKm areas. Communities require knowledge and skills to choose the quality and types of tree species to maintain ecological balance in their HKm area. The trees should be species that have higher ecological impacts to strengthen soil and water conservation in their HKm lands, for example Tectona grandis, Swietenia mahagony, Gnetum gnemon, Mangofera indica. The communities also need supports to choose the species with high economic value and which are easy-to-be-marketed, for example Durio zibethynus (Wulandari et al. 2014). The other needs are choosing quality seedlings for optimal harvesting results.

4. Discussion

Two key contributions could be derived from this paper based on the AHP analysis of community preferences for facilitation in SF program at level 2 (prioritized stakeholders) and level 3 (types of and timing for facilitation). The analysis at these levels is linked to level 1 which is the purpose of this study to understand community facilitation for sustainability of the SF program.

This study identified the top three priorities for facilitation in all three subjects within communities, referred to as HKm’s individual members, groups, and non-members. The findings of this paper confirms the existing literature which underlines the need for facilitating communities to support SF programs. Communities require facilitation, for strengthening community institutions and strengthening livelihood support (Gupta and Koontz 2019, Wollenberg et al., 2006). This paper further adds to this knowledge by showing the levels of priorities for facilitation and support among FUGs that have long been established. The scale of priorities begin from the most important subjects to be training, which are in the following order: HKm individual members, HKm groups, and other villagers (non-HKm members).

The finding shows that the communities involved in SF programs perceive that every individual member, including non-elite members, should be facilitated. For example, they should also be supported to attend trainings and then share the new skills or knowledge to the group, rather the common practice of facilitating group leadership to attend such trainings. In this study, the findings did not specifically point to the elite, but rather the respondents point out the domination of specific members of the FUGs who have more opportunities than other members, such as the repeated attendance at trainings outside the village. This importance of facilitation for individual members of HKm indicates the emergence of awareness about equity and issues of power in community groups. This finding is consistent with literature that underlines the importance of avoiding elite capture, which further strengthens the dominance of elites within community groups (Persha and Andersson, 2014). Thus, the attempts to facilitate communities should strengthen the capacities of communities, not only by selecting the elites for trainings, but also supporting the less empowered individual members of an FUG.

The finding on prioritizing facilitations for individual group members also sheds light on the potential indirect results of SF programs to empower the community, which may only emerge after certain periods of involvement in an SF program. This paper shows that HKm members are not only interested in livelihood benefits from SF programs but also showed greater interests in the equity aspects within the groups. For example, they supported the notion to provide opportunities for every member to build their capacities, particularly individual members who were given less opportunities in the past. This demand, to a certain extent, provides a signal of empowerment which might emerge from their participation in the SF program. This finding is relevant to other studies which have underlined that external facilitation should lead communities to be able to help themselves (Barnes and Laerhoven, 2013).

The finding from this study shows that communities consider external actors (i.e. facilitators from NGOs and universities and local and national government), which are often positioned as the providers of facilitation, are also in need of support. This interesting finding shows that SF indeed involves dynamic interactions between communities and external actors whereas social learning occurs to support adaptiveness (Lawrence, 2007; Lawrence et al., 2009). This finding supports the argument that facilitating ‘enablers’ is also a key for the sustainability of the SF program (Duguma et al., 2018). In this study, enablers could be community facilitators from NGOs and universities as well as government agencies which support communities through targeted policies. This finding also supports other studies which found that facilitators, from NGOs and other individual champions within local government, still require further support (Kurniasih, 2016). This paper adds to this literature by showing the continuing importance of facilitators, in their direct engagement with communities (i.e. NGOs and universities), followed by the emphasis on SF support from government agencies.

This study shows that the most desirable type of facilitation by the respondents are in developing entrepreneurship capacity, followed by developing technical skills, and then strengthening organizations. This finding is consistent with the general desire of practitioners supporting SF in Indonesia. In a national level meeting involving stakeholders of SF in Indonesia, discussions emerged about the need to prioritize entrepreneurship as a bridge to fulfill the livelihood needs of communities (FKKM, 2014). The finding from this paper is interesting because several studies highlight that strengthening community institutions deems to be the most pressing issues of SF in other countries (e.g. Pokharel et al., 2014). In the Indonesian HKm case, Suhirman et al. (2012) also found that many HKm groups are not yet effective in implementing SF, and that facilitation for strengthening organizations should be one top priority. However, this study found that communities only prioritized this type of facilitation in the third place on the hierarchy of priorities, after entrepreneurship and skills.

The finding shows that entrepreneurship facilitation should be provided for groups which are newly established and for groups that have been established for more than 10 years. It is not clear yet whether placing entrepreneurship as the main priority indicates that the FUGs interviewed for this research might have moved beyond the stages of building a mature organization, or whether it reflects their continuing emphasis on livelihood aspects. In this study, the result shows that both explanations could be the reasons behind the community priorities on entrepreneurship facilitation. Further studies are needed to explain this inconclusive result.

In Indonesia, the goals of facilitation are stated in Indonesian regulations such as Minister of Forestry Regulation 29/2013, and then further detailed in the Director General of Social Forestry and Environmental Partnership 1/2009. Community facilitation is expected to help efforts in sustaining forests, while improving community welfare. The last priority to facilitation for ecological activities indicates that the goal of sustainable forest management has not entered into the top priority of the community.

The lessons from the HKm program in Lampung shows that the community has specific preferences for facilitation from external actors with an emphasis on building community entrepreneurship to improve their welfare rather than merely strengthening community institutions. This emphasis on building entrepreneurship skills gives insight that community might perceive, up to the point of time when this study is conducted, that the benefits from SF are limited to improving their welfare. They consider the major hindrance is their entrepreneurship skills rather than technical skills or institutional weakness within community organization. However, the finding from this study is potentially only applied to the type of SF in the protected forest area where communities managing SF lands are restricted to only using non-timber forest products. The findings on community preference for facilitation in this type of forest area (protection forest) may not apply to other types of SF programs (e.g. HKm in production forest areas) where communities are allowed to harvest timber in their plots.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents the priorities of key stakeholders for facilitation in the SF program in Lampung. The finding from this study sheds light about the emerging discussions in social forestry literature on community entrepreneurship and the needs to strengthen capacities of support actors, among others.

The paper shows the emerging new interests of communities to issues beyond securing livelihoods through SF programs or strengthening the organization. The emerging interest of community members on building the capacities of the weaker members of FUG provides signals that, after a certain period of time, SF programs may provide building blocks for empowering communities. For example, we noted in this study that there is an increasing community awareness about improving equity within groups. Nevertheless, this aspect is beyond the scope of this study, pointing to the need for future studies to investigate whether and how external support could help to build equity for FUG members.

The paper also shows continuing community interest in improving entrepreneurship capacity for FUGs which have been established for more than 10 years. Further study is needed to understand the specific needs of FUGs established at different periods. This paper also raises an important finding of what types of support are needed for NGOs and external facilitators from universities and government agencies. Future study in this area could lead to practical knowledge on policy design to enable effective support for external actors which facilitate communities in the SF program.

This research is limited to a focus on the preference of communities as the main stakeholder implementing an SF program. Future research to identify the preference of other stakeholders, including external facilitators, is important to understanding whether there is a gap between community preference and other stakeholder preferences for community facilitation in the SF program.

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix 1

QUESTIONAIRES - COMMUNITY PREFERENCES FOR FACILITATION IN SF PROGRAM

| 1. | Name of respondent | : | |

| 2. | Respondent no. | : | |

| 3. | Farmer/HKm Group Name | : | |

| 4. | Date of group establishment | : | |

| 5. | Address (Village) | : | |

| 6. | Date of interview | : | |

| 7. | Interviewer | : | |

| 8. | Checker/Verifier | : | |

| 9. | Remarks | : |

Section 1. Respondent’s Characteristics

- Age

- What is the respondent’s age on the last birthday? Years [ ] [ ]

- Marital status? single [ ] widowed [ ]

married [ ] separate [ ]

2. Education

- What is the highest grade you had finished in school?

[ ] No formal education

[ ] Elementary School

[ ] Junior High School

[ ] Senior High School

[ ] University/ College

Section 2. Socio-Economic Factors

- Family size

3.1. How many persons are living together in respondent’s house ?

| No | Name | Age (yrs) | Sex | Status | Relationship | Education | Attainment | Remarks |

| 1.2.3.4.5.6. |

- Occupation/ Main source of family income

- What is the respondent’s primary occupation/ main source of income?

[ ] Non farming/ others (specify) : ………………..

[ ] Farming

- Secondary occupation (please specify) : ………………………..

- Family Gross Income

- What is the respondent’s estimated family monthly gross income?

Farm income Rp ……………….

Off-farm income Rp ……………….

Total income Rp ………………

Family expenses Rp……………….

Net family income Rp ………………

Section 3. HKm Management

6. Size of “HKm” as land holding

6.1. What is the total size of your “HKm” land? …..ha

6.2. Do you always have (plant/utilise) the same tree species in your “HKm” land? yes [ ] no [ ]

6.3. What is the reason you have the same/ different tree species?

6.4. What is the technology you use to maintain your “HKm” land?

7. How much do you spend to maintain your “HKm” land (monthly) ?

8. What forest products you harvest from your “HKm” land? (tree(s)/fruit(s)/crop/vegetable(s))

9. Forest product harvesting

9.1. Purpose of harvesting : [ ] no harvest

- [ ] to fulfil household daily needs

- [ ] mainly to fulfil household needs, the rests are sold to market

- [ ] to sell all products to the market

- [ ] mainly to sell to the market, the rests are for daily needs

9.2. If products are sold to the market, location and distance of market ?

9.3. Income from product harvesting (average per year or per month) :

Products harvested Units Rp

_______________________ ___________ _____________

_______________________ ___________ _____________

_______________________ ___________ _____________

_______________________ ___________ _____________

_______________________ ___________ _____________

_______________________ ___________ _____________

Section 4. HKm Institution

10. Membership in any other organization. [ ] Yes [ ] No

If yes, please specify name of the organization/association and your position.

Name of organization/ association Position

____________________________ __________________

____________________________ __________________

____________________________ __________________

11. Information sources

11.1. What information sources do you use to manage your “HKm” land?

[ ] no information source [ ] neighbours/ friends/ hereditary

[ ] worker field [ ] television

[ ] radio [ ] book/s

[ ] newspaper or magazine/s [ ] combination of them

11.2. Do you have meeting with other farmers to get that information? How many time?

11.3. Do you have meeting with field extension workers to get that information? How many time?

Section 5. Training

12. Training

12.1. Number of training attended:

Skill development

Title of training/workshop & Purpose Year/Duration Follow up

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

Entrepreneurship

Title of training/workshop & Purpose Year/Duration Follow up

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

Strengthening organization

Title of training/workshop & Purpose Year/Duration Follow up

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

Ecological Conservation

Title of training/workshop & Purpose Year/Duration Follow up

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

12.2. Training that needed by public:

Skill development

Title of training/workshop & Purpose Year/Duration Follow up

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

Entrepreneurship

Title of training/workshop & Purpose Year/Duration Follow up

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

Strengthening organization

Title of training/workshop & Purpose Year/Duration Follow up

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

Ecological Conservation

Title of training/workshop & Purpose Year/Duration Follow up

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

12.3. Training that needed by NGO/Univ:

Skill development

Title of training/workshop & Purpose Year/Duration Follow up

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

Entrepreneurship

Title of training/workshop & Purpose Year/Duration Follow up

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

Strengthening organization

Title of training/workshop & Purpose Year/Duration Follow up

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

Ecological Conservation

Title of training/workshop & Purpose Year/Duration Follow up

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

12.4. Training that needed by Government:

Skill development

Title of training/workshop & Purpose Year/Duration Follow up

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

Entrepreneurship

Title of training/workshop & Purpose Year/Duration Follow up

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

Strengthening organization

Title of training/workshop & Purpose Year/Duration Follow up

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

Ecological Conservation

Title of training/workshop & Purpose Year/Duration Follow up

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

| Which HKm subject is prioritised/more important to be facilitated? | The level of importance: in which level ? | ||

| Individual | HKm Group | ||

| Individual | Public | ||

| Individual | NGO/Univ | ||

| Individual | Govt | ||

| HKm Group | Public | ||

| HKm Group | NGO/Univ | ||

| HKm Group | Govt | ||

| NGO/Univ | Govt | ||

- Comparative Level 2

- Comparative Level 3

Individual

| Which type of facilitation/training is more important? | The level of importance: in which level ? | ||

| Skill | Entrepreneurship | ||

| Skill | Strengthening Organization | ||

| Skill | Conservation Activities | ||

| Entrepreneurship | Strengthening Organization | ||

| Entrepreneurship | Conservation Activities | ||

| Strengthening Organization | Conservation Activities | ||

HKm Group

| Which type of facilitation/training is more important? | The level of importance: in which level ? | ||

| Skill | Entrepreneurship | ||

| Skill | Strengthening Organization | ||

| Skill | Conservation Activities | ||

| Entrepreneurship | Strengthening Organization | ||

| Entrepreneurship | Conservation Activities | ||

| Strengthening Organization | Conservation Activities | ||

Public (other villagers)

| Which type of facilitation/training is more important? | The level of importance: in which level ? | ||

| Skill | Entrepreneurship | ||

| Skill | Strengthening Organization | ||

| Skill | Conservation Activities | ||

| Entrepreneurship | Strengthening Organization | ||

| Entrepreneurship | Conservation Activities | ||

| Strengthening Organization | Conservation Activities | ||

NGO/Univ

| Which type of facilitation/training is more important? | The level of importance: in which level ? | ||

| Skill | Entrepreneurship | ||

| Skill | Strengthening Organization | ||

| Skill | Conservation Activities | ||

| Entrepreneurship | Strengthening Organization | ||

| Entrepreneurship | Conservation Activities | ||

| Strengthening Organization | Conservation Activities | ||

Government

| Which type of facilitation/training is more important? | The level of importance: in which level ? | ||

| Skill | Entrepreneurship | ||

| Skill | Strengthening Organization | ||

| Skill | Conservation Activities | ||

| Entrepreneurship | Strengthening Organization | ||

| Entrepreneurship | Conservation Activities | ||

| Strengthening Organization | Conservation Activities | ||

Download Citation

Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)BibTeX

- Barnes, C. & Van Laerhoven, F. (2013). Helping to self-help: External interventions to stimulate local collective action in Joint Forest Management, Maharashtra, India. International Forestry Review, 15(1), 1-17.

- Barsimantov, A. J. (2010). Vicious and Virtuous Cycles and the Role of External Non-Government Actors in Community Forestry in Oaxaca and Michoacan, Mexico. Human Ecology: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 38(1), 49-63.

- Dongre, P. (2011). Role of social forestry in sustainable development a micro level study. Int J Soc Sci Humanit Stud, 3(1), 351–364.

- Duguma, A.L, Minang, A.P, Foundjem-Tita, D, Makui, P, & Piabuo, M.S. (2018). Prioritizing enablers for effective community forestry in Cameroon. Ecology & Society, 23(3), 404-419.

- FKKM (2014). Pengelolaan hutan berbasis masyarakat: status kini dan masa depan. RECOTFC, Bangkok, Thailand.

- Gupta, D. & Koontz, M. T. (2019). Working together? Synergies in government and NGO roles for community forestry in the Indian Himalayas. World Development, 114, 326-340.

- Kurniasih, H. (2016). Multi-level transitions in the community forestry system for development in Indonesia. Ph.D. thesis. The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia.

- Lawrence, A. (2007). Beyond the second generation: Towards adaptiveness in participatory forest management. CAB Reviews: Perspectives in Agriculture, Veterinary, 2(28).

- Lawrence, A., Anglearke, B., Frost, B., Nolan, P., & Owen, R. (2009). What does community forestry mean in a devolved Great Britain? International Forestry Review, 11(2), 281-297.

- Ling, S., Smith, H., Xaysavongsa, L., & Laity, R. (2018). The Evolution of Certified Teak Grower Groups in Luang Prabang, Lao PDR: An Action Research Approach, Small-scale Forestry, 17, 343–360.

- Mårald, E., Sandström, C., Rist, L., Rosvall, O., Samuelsson, L., & Idenfors, A. (2015). Exploring the use of a dialogue process to tackle a complex and controversial issue in forest management. Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research, 30(8), 749-756.doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02827581.2015.1065343

- McDougall, C.; Pandit, B.H.; Banjade, M.R.; Paudel, K.P.; Ojha, H.; Maharjan,M.; Rana, S.; Bhattarai, T.; & Dangol, S. (2009). Facilitating forests of learning: Enabling an adaptive collaborative approach in community forest user groups: a guidebook. Bogor, Indonesia: Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR).

- Moeliono, M., Thuy, P., Waty Bong, I., Wong, G., & Brockhaus, M. (2017). Social Forestry - why and for whom? A comparison of policies in Vietnam and Indonesia. Forest and Society, 1(2), 78-97. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.24259/fs.v1i2.2484

- Mvondo, S. & Oyono, R. P. (2004). An Assessment of Social Negotiation as a Tool of Local Management: A Case Study of the Dimako Council Forest, Cameroon. Scand. J. For, Res., 19(4), 78-84.

- Nawir, A. A. (2011). Satu Dasawarsa Perjalanan Kemitraan Masyarakat—perusahaan Hutan di Indonesia: Studi Kasus Finantara Intiga, Sanggau, Kalimantan Barat. Jurnal Kehutanan Masyarakat, 3 (1), 6–31.

- Persha, L. & Andersson, K. (2014). Elite capture risk and mitigation in decentralized forest governance regimes. Global Environmental Change, 24, 265-276.

- Pokharel, K. B., Branney, P., Nurse, M. & Malla, B. Y. (2007). Community Forestry: Conserving Forests, Sustaining Livelihoods and Strengthening Democracy. Journal of Forest and Livelihood, 6(2), 8-19.

- Saaty, T.L. (2008). Decision making with the analytic hierarchy process. Int. J. Services Sciences, 1(1), 83-98.

- Sapkota, P, Keenan, R. J. & Ojha, H. R. (2018). Community institutions, social marginalization and the adaptive capacity: A case study of a community forestry user group in the Nepal Himalayas. Forest Policy and Economics, 92, 55-64.

- Suhirman, Alamsyah, Z., Zaini, A., Sulaiman, dan Nikoyan, A., (2012). Studi Perencanaan dan Penganggaran Bagi Pengelolaan Hutan Berbasis Masyarakat di Indonesia: Studi Kasus Provinsi Jambi, Kalimantan Barat, Nusa Tenggara Barat, Sulawesi Tenggara. Laporan Utama Sebagai Hasil Studi Lapangan. Kemitraan (Bagi Pembaruan Tata Kepemerintahan di Indonesia).

- Wollenberg, E., Colchester, M., Mbugua, G., & Griffiths, T. (2006). Linking social movements: how international networks can better support community action about forests. International Forestry Review, 8(2),265-272.

- Wulandari, C. & Inoue, M. (2018). The Importance of Social Learning for the Development of Community Based Forest Management in Indonesia: The Case of Community Forestry in Lampung Province. Small-scale Forestry, 17, 361–376.

- Wulandari, C. & Budiono, P. (2015). Social Capital Status on HKm Development in Lampung. 3rd INAFOR'S International Conference of Indonesia Forestry Researchers, 8 p.

- Wulandari, C., Yuwono, B. S., Budiono, P. & Herwanti, S. (2014). Adoption of Agroforestry Patterns and Crop Systems Around Register 19 Forest Park, Lampung Province, Indonesia. Jurnal Manajemen Hutan Tropika, 2(20), 2089-2063.

References

Barnes, C. & Van Laerhoven, F. (2013). Helping to self-help: External interventions to stimulate local collective action in Joint Forest Management, Maharashtra, India. International Forestry Review, 15(1), 1-17.

Barsimantov, A. J. (2010). Vicious and Virtuous Cycles and the Role of External Non-Government Actors in Community Forestry in Oaxaca and Michoacan, Mexico. Human Ecology: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 38(1), 49-63.

Dongre, P. (2011). Role of social forestry in sustainable development a micro level study. Int J Soc Sci Humanit Stud, 3(1), 351–364.

Duguma, A.L, Minang, A.P, Foundjem-Tita, D, Makui, P, & Piabuo, M.S. (2018). Prioritizing enablers for effective community forestry in Cameroon. Ecology & Society, 23(3), 404-419.

FKKM (2014). Pengelolaan hutan berbasis masyarakat: status kini dan masa depan. RECOTFC, Bangkok, Thailand.

Gupta, D. & Koontz, M. T. (2019). Working together? Synergies in government and NGO roles for community forestry in the Indian Himalayas. World Development, 114, 326-340.

Kurniasih, H. (2016). Multi-level transitions in the community forestry system for development in Indonesia. Ph.D. thesis. The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia.

Lawrence, A. (2007). Beyond the second generation: Towards adaptiveness in participatory forest management. CAB Reviews: Perspectives in Agriculture, Veterinary, 2(28).

Lawrence, A., Anglearke, B., Frost, B., Nolan, P., & Owen, R. (2009). What does community forestry mean in a devolved Great Britain? International Forestry Review, 11(2), 281-297.

Ling, S., Smith, H., Xaysavongsa, L., & Laity, R. (2018). The Evolution of Certified Teak Grower Groups in Luang Prabang, Lao PDR: An Action Research Approach, Small-scale Forestry, 17, 343–360.

Mårald, E., Sandström, C., Rist, L., Rosvall, O., Samuelsson, L., & Idenfors, A. (2015). Exploring the use of a dialogue process to tackle a complex and controversial issue in forest management. Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research, 30(8), 749-756.doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02827581.2015.1065343

McDougall, C.; Pandit, B.H.; Banjade, M.R.; Paudel, K.P.; Ojha, H.; Maharjan,M.; Rana, S.; Bhattarai, T.; & Dangol, S. (2009). Facilitating forests of learning: Enabling an adaptive collaborative approach in community forest user groups: a guidebook. Bogor, Indonesia: Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR).

Moeliono, M., Thuy, P., Waty Bong, I., Wong, G., & Brockhaus, M. (2017). Social Forestry - why and for whom? A comparison of policies in Vietnam and Indonesia. Forest and Society, 1(2), 78-97. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.24259/fs.v1i2.2484

Mvondo, S. & Oyono, R. P. (2004). An Assessment of Social Negotiation as a Tool of Local Management: A Case Study of the Dimako Council Forest, Cameroon. Scand. J. For, Res., 19(4), 78-84.

Nawir, A. A. (2011). Satu Dasawarsa Perjalanan Kemitraan Masyarakat—perusahaan Hutan di Indonesia: Studi Kasus Finantara Intiga, Sanggau, Kalimantan Barat. Jurnal Kehutanan Masyarakat, 3 (1), 6–31.

Persha, L. & Andersson, K. (2014). Elite capture risk and mitigation in decentralized forest governance regimes. Global Environmental Change, 24, 265-276.

Pokharel, K. B., Branney, P., Nurse, M. & Malla, B. Y. (2007). Community Forestry: Conserving Forests, Sustaining Livelihoods and Strengthening Democracy. Journal of Forest and Livelihood, 6(2), 8-19.

Saaty, T.L. (2008). Decision making with the analytic hierarchy process. Int. J. Services Sciences, 1(1), 83-98.

Sapkota, P, Keenan, R. J. & Ojha, H. R. (2018). Community institutions, social marginalization and the adaptive capacity: A case study of a community forestry user group in the Nepal Himalayas. Forest Policy and Economics, 92, 55-64.

Suhirman, Alamsyah, Z., Zaini, A., Sulaiman, dan Nikoyan, A., (2012). Studi Perencanaan dan Penganggaran Bagi Pengelolaan Hutan Berbasis Masyarakat di Indonesia: Studi Kasus Provinsi Jambi, Kalimantan Barat, Nusa Tenggara Barat, Sulawesi Tenggara. Laporan Utama Sebagai Hasil Studi Lapangan. Kemitraan (Bagi Pembaruan Tata Kepemerintahan di Indonesia).

Wollenberg, E., Colchester, M., Mbugua, G., & Griffiths, T. (2006). Linking social movements: how international networks can better support community action about forests. International Forestry Review, 8(2),265-272.

Wulandari, C. & Inoue, M. (2018). The Importance of Social Learning for the Development of Community Based Forest Management in Indonesia: The Case of Community Forestry in Lampung Province. Small-scale Forestry, 17, 361–376.

Wulandari, C. & Budiono, P. (2015). Social Capital Status on HKm Development in Lampung. 3rd INAFOR'S International Conference of Indonesia Forestry Researchers, 8 p.

Wulandari, C., Yuwono, B. S., Budiono, P. & Herwanti, S. (2014). Adoption of Agroforestry Patterns and Crop Systems Around Register 19 Forest Park, Lampung Province, Indonesia. Jurnal Manajemen Hutan Tropika, 2(20), 2089-2063.