This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Examining forest economies: A case study of silk value chain analysis in Wajo District

Corresponding Author(s) : Makkarennu Makkarennu

Forest and Society,

Vol. 3 No. 1 (2019): APRIL

Abstract

Keywords

Full text article

1. Introduction

Natural silk takes place through a series of agro-industry activities, beginning with the mulberry plant, which consists of the feed for silkworm, requiring nursing and maintenance of silkworms (Bombyx mori, L), followed by the processing of cocoons into yarn (spinning yarn), the weaving of cloth, and finally to the marketing of silk fabrics. This business falls into the category of the home industry market, and can be a lucrative product for rural livelihoods. The industry is categorized as relatively easy to be taxed, applies a fairly simple technology, and while it is labor intensive, results in relatively rapid generating incomes of high economic value. Natural farming activities can also take place in parallel, presenting possibilities to rehabilitate land and improve soil conservation. Furthermore, the silk farming industry can help to increase the load capacity and productivity of land, especially on lands that have not been optimally utilized (Sihar, 2008).

One of the well-known silk-producing regions in Indonesia is Wajo District, South Sulawesi. The region is also site to social forestry programs in South Sulawesi. In its implementation, social forestry is based on community-based forest management by paying attention to the following principles: benefits and sustainability, self-reliance, togetherness and partnership, intersectoral integration, in approaches that are gradual, sustainable, and adaptive (Hakim, et al., 2010). The Wajo District is famous as a silk region because of the longstanding and skillful abilities of people in the region in trading silk. Silk is one of the leading commodities because managing production has been carried out from generation to generation, and are either managed as a side activity, as a home industry venture, or even as a medium-scale industry (Sihar, 2008). In the 1960s and 1970s the silk weaving industry in the Wajo district experienced its peak, but was followed by a period of precipitous decline due to the difficulty of obtaining high quality raw materials. This ultimately affected results on the production side of weaving and also affected market demand. Renewed weaving industry activities began to develop in the late 1990s when imported raw materials were allowed to re-enter and the market began to experience regeneration (Sihar, 2008).

Production from silk farmers has fluctuated in recent years (Harbi, et al., 2015). This not only has had an impact on improving the economy of these communities, but also interacts with the prevailing prices on the market. Natural silk production, for example, experienced a rapid increase in 2013, jumping to a level of 3,000 kg; but in 2014 experience a drastic decline falling below 500 kg.

The decline in silk production was caused by changes in crop prices, from which the mulberry croplands for silk food were being converted to corn production. This was due to a brief spike in corn prices presenting more promising possibilities in the short term in comparison to silk. In addition, the supply of silkworm seeds to farmers had also been of a fairly low quality, and as a result affected the quality of the yarn produced (Nuraeni, 2017). Farmers have so far only acted by accepting prices (price takers) from traders who control the market (as price makers), indicating the weak bargaining position of rural farmers.

Furthermore, constraints on silk are not only in terms of production, but also in terms of marketing. As with other farmers, they tend to be dependent on more rapid rates of return because of urgent needs. This broad trend is what collectors or other actors use as bargaining power to reduce the price of yarn in the market. At present, the price of silk yarn is quite low at the farmer level, whereas when compared to yarn at the market price, the trader receives a higher price. Farmers have so far only acted as price takers while traders who control the market become price makers indicating the weak bargaining position of farmers.

Based on this background of the silk industry and conditions observed in Wajo, this research seeks to take a closer look at the value chain to help understand how to reshape more efficient market processes by identifying the actors who are participating across the value chain. In particular the analysis seeks to identify those who benefit from production activities at stages from upstream to downstream. Thus, the purpose of this research is 1) to map the actors of the silk commodity business, 2) to determine the activities of business actors, 3) to analyze the calculation of financial ratios (marketing margins and profits) of business actors.

2. Method

2.1 Data analysis

Value chain analysis examines activities that produce additional value across the various stages of production (Widarsono, 2009). One of the basic assumptions in value chain analysis is the development of markets that aim to have a positive impact on a broader society by providing income or improved employment opportunity through their participation in developing the market. This means encouraging synergy between farmers and/or producers with post-harvest processing entrepreneurs so that they are unwittingly able to increase the income of the people in the governance of the value chain. With the integration of the silk sector with the community home industry sector, a value chain might form that will provide additional income and absorb labor with the presence of actors in the value chain. However, before beginning to conduct the value chain analysis it is necessary to decide what sub-sectors, products, or commodities should be prioritized for analysis (ACIAR, 2012).

In analyzing the value chain, especially in silk commodities in the Wajo District, the analytical method used is a descriptive method. The steps in using this method are (i) descriptively identifying data and information obtained from the results of in-depth interviews with stakeholders or related parties (farmers, local traders, weavers, and local government) and (ii) mapping the value chain to identify precisely the actors who are participating across the value chain. These research goals answer the overall research question: (1) who are the actors of the silk commodity business, (ii) what are the activities of business actors, and (iii) how do the marketing margins and profits of business actors get distributed?

Mapping the value chain is a major step in helping to answer questions about the linkages in value chain governance. Value chain mapping objectives include obtaining a fundamental review of the value chain as a framework for the overall value chain analysis carried out, identifying barriers and solutions that may be taken at various levels in the value chain, identifying the position of each actor in the value chain, demonstrating interdependence between actors and processes in the value chain, and creating awareness for actors to identify more than the scope of their involvement in the value chain. The steps include the following:

- Identifying actors who play a role: Identifying actor relationships that influence governance structures in the value chain is essential. The value chain does not only calculate the marketing margins of each actor but also determines the magnitude of the distribution of value added received by each actor along the Silk value chain in the Wajo District, which aims to find out where the biggest beneficiaries are located across the value chain. Each value chain has its own processes and activities, and knowing which activities each actor is involved with, helps to identify potential efforts to increase the value of a product. This was done by interviewing farmers, local traders, weavers and silk clothing stores.

- Calculating financial ratios (marketing and financial margins): By interviewing the actors who are participating in the value chain, financial ratios could be determined. In addition, observation is also needed to better understand the activity of the farmer. The marketing margin can be determined by the mathematical formula as follows (Popoko, 2013):

Information:

Mji= Marketing margin at the first institution level (Rp)

Pri = Prices at a certain level (Rp)

Pfi = Prices at the next level (Rp)

bi = Marketing costs at the first level (Rp)

Ki = Marketing advantage at the first institution level (Rp)

The value chain does not only calculate the marketing margins of each actor but also determines the magnitude of the distribution of value added received by each actor along the Silk value chain in the Wajo District, which aims to find out where the biggest beneficiaries are located. The profit margin formula is as follows:

Information:

π = Benefits received by every actor (actor)

Pa = Selling price in each actor (Rp.)

Pb = Price of buying products in each Actor (Rp)

C = Marketing costs for eachactor (Rp)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Map of silk business actors

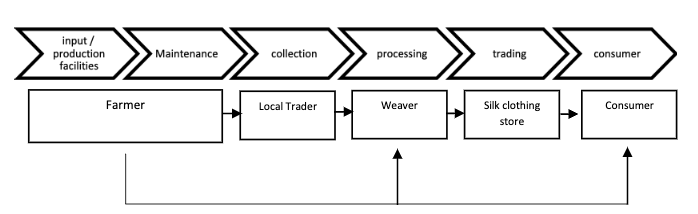

The silk business actors have their respective roles in a series of activities in producing the products. Silk value chain actors are presented in Figure 1. The various roles include:

- Farmers. Farmers are a group of people who use land daily to support their needs. The number of farmer groups in Sabbangparu sub-district include 7 groups. Farmers as silk entrepreneurs act as coarse yarn producers. Farmer activities include maintenance and spinning the yarn into coarse yarn.

- Local Traders: Local traders are buyers of coarse silk thread from farmer groups located in the Salojampu market (sub-district market). Local traders act as the producers of fine yarn silk and as fine yarn sellers. Local traders get raw materials from coarse yarn from farmers, then process coarse yarn into fine yarn through the process of bleaching and cooking. After becoming fine thread, local traders then sell it at the Salojampu market.

- Weavers / craftsmen: Weavers / craftsmen are people who are engaged in making products from silk thread. Weavers develop products from fine yarn raw materials. There are various products including cloth, clothing, and others. Products are also developed by craftsmen in accordance with the order.

- Shops for silk clothing: A silk clothing store is a place to buy and sell silk products. The silk shop offers a variety of woven products from craftsmen.

Figure 1. Map of Silk Commodity Business Actors

3.2 Activities of Silk Business Actors

3.2.1 Main Activities

The main activity is a process of physical product creation, marketing and transfer to buyers and after-sales service. The main activity of business actors in silk commodities begin from the farmers with their roles as providers or producers of coarse yarn from silkworms. At the next level of activity, are local traders where the main activity is buying silk thread from farmers and selling it to weavers / craftsmen. Furthermore, the activities of weavers / craftsmen manage the process of turning threads into finished goods such as sarongs and others. Then at the final level of the main activity of silk commodity business actors are the clothing stores with their activities as weavers. The activities of silk entrepreneurs are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Main Activities of Business Actors

| Inbound Logistics | Operation/Process | Outbo u nd Logistics | Marketing, Sales and Services |

| Farmers | |||

| Silk maintenance equipment | Hatching / incubating silkworm eggs | Weighing together silk thread | In general, farmers do not carry out marketing activities |

| Acceptance of silkworm eggs | Maintenance of silkworms | Payment of the agreed price | |

| Taking mulberry leaves | Cocoon | Coarse yarn collection in the head of the farmer group | |

| Pressing silk thread | Coarse thread storage | ||

| Yarn twisting | |||

| Release | |||

| Bleaching and coloring of silk thread | |||

| Local Traders | |||

| Weighing silk thread | Silk thread bleaching | Loading into motorized vehicles | Sales of loose threads in the Salojampu market |

| Payment for the purchase of silk thread | Bringing to the sale location (salojampu market) | ||

| Weighing at trade locations | |||

| Payment of the agreed price | |||

| Weaver | |||

| Purchase of yarn in the local market | Silk weaving | Bring to a silk sales shop | There is no marketing information between weavers and buyers. The weaving will be done when there is an order from a silk sales shop |

| Weaving tools | Use of motorized vehicles | ||

| Silk Clothing Store | |||

| Purchase products from weavers | Sorting out products | Delivering goods through the sales shop | Loose sales at the store |

| Payment according to price agreement | Pricing on products | Through shipping to outside Wajo district | Product information through the exhibition of regional superior products |

| Payment according to price agreement between seller and consumer | |||

3.2.2 Supporting Activities

Supporting activities help the company as a whole by providing infrastructure or inputs that enable key activities to be carried out on an ongoing basis. Supporting activities of silk commodity business actors begin with farmers planting mulberry plants that feed silkworms. Supporting activities are then carried out by local traders with their activities supporting infrastructure to facilitate the distribution of silk thread from farmers to weavers / craftsmen.

Supporting activities carried out by weavers / craftsmen possess knowledge in weaving, they own vehicles, and establish relationships with silk clothing stores, as well as supporting activities at the final actor level, namely the silk clothing store. This includes involvement at local product exhibitions in the city of Makassar and in other cities. Supporting activities of silk entrepreneurs are presented in Tables 2, 3, 4, 5.

Table 2. Farmer Support Activities

| Inbound Logistics | Operation/Process | Outbond Logistics | Marketing, Sales and Services |

| Infrastructure | |||

| Picking up mulberry leaves on the home page | Maintenance of silkworms is done at home | Coarse silk threads are collected in a plastic bag | In general, farmers do not carry out marketing activities |

| Human Resources | |||

| Farmer ability to cultivate mulberry is gained from experience | Expertise is obtained from learning outcomes from parents | In general, there is no special ability or expertise in removing goods | In general, farmers do not understand aspects related to marketing |

| The result of training in silkworm cultivation | |||

| Technological Development | |||

| Generally, there is no technology used in this activity | The technology used is still quite simple, equipment made of wood | Generally, there is no technology used in this activity | Generally, there is no technology used in this activity |

| Procurement | |||

| Taking mulberry leaves using household appliances | Procurement of silkworm maintenance equipment | Weighing equipment purchased by farmers | In general, farmers do not carry out marketing activities |

| Acceptance of silkworm eggs from the local district agency | Procurement of coloring material | ||

For supporting activities, in terms of infrastructure for logistics, farmers require a field that is large enough to plant mulberry. Furthermore, the distance from the location to the maintenance area must not be too far. In addition, the process or maintenance of silkworms is done at home. For outbound logistics, first, coarse threads are collected in a container before being marketed. Meanwhile, in terms of marketing, farmers do not carry out these activities because farmers only wait for local traders to collect the yarn.

As with human resources for internal logistics, farmers only have the ability to cut mulberry leaves using knives when harvesting mulberry. In addition, in terms of maintenance, silkworm cultivation skills are derived from the experience of more experienced farmers and from trainings that have been conducted. In terms of outbound logistics, farmers do not have special abilities. This is because the expenditure of goods is only in the form of collection of silk thread so that it does not require specialized knowledge. This is similar in terms of marketing that there is no special ability in marketing goods, because farmers only wait for local traders to pick up the goods.

Whereas in terms of technology, farmers only use equipment that is quite simple, in the form of self-maintenance shelves made from wood and bamboo, cocoon making made with bamboo-based material, and spinning equipment purchased from equipment stores. Although farmers conduct supporting activities in terms of procurement, they only need equipment such as knives or machetes, maintenance tools, yarn coloring materials and scales to weigh the yarn.

Table 3. Supporting activities of local traders

| Inbound Logistics | Operation/Process | Outbo u nd Logistics | Marketing, Sales and Services |

| Infrastructure | |||

| The facilities passed or accessibility to the location of the farmers are quite good | Processing of coarse yarn into fine yarn is done at the merchant's house | Transport of finished yarn to market locations using motorized vehicles | Infrastructure in terms of marketing products only through storefronts in yarn sales shops in the Salojampu market |

| Location of selling yarn in the form of buildings in the Salojampu market | |||

| Human Resources | |||

| In general, there is no specific qualification in the collection of yarn to farmers because the trust between traders and farmers is intertwined | Knowledge gained by traders in yarn bleaching and coloring is obtained from parents or passed down through generations | In general, there is no specific qualification in issuing merchant products | In general, there are no specific qualifications and activities in marketing merchant products because they are only in the form of loose sales on the market |

| Technological Development | |||

| Use of motorized vehicles in the transportation and collection of goods for farmers | The technology used is quite simple in the form of pots, stoves, and natural ingredients in the form of leaves used in coloring | In general, local traders do not use technology in removing goods | In general, traders do not use certain technologies in terms of marketing |

| Procurement | |||

| Provision of merchant operations is carried out individually | Provision of raw materials for bleaching and coloring | Operational provision is carried out individually and based on the trader's capital | There is no special activity in marketing because it is only limited to free sales in the Salojampu market |

In terms of infrastructure of local traders, they are supported by facilities or accessibility in the form of a fairly decent road to the location of farmers. In addition, local traders are also supported by rather vibrant sales locations in the form of buildings in the Salojampu market; whereas in marketing goods, local traders have a storefront at the sales location. In supporting activities in terms of human resources, local traders are supported by knowledge gained from parents and neighboring friends in terms of yarn bleaching whereas in terms of marketing, local traders obtain knowledge from the experiences gained.

In addition, in terms of technology development, local traders only use motorized vehicles to support the transportation and retrieval of goods from farmers. For the process of yarn bleaching, local traders use technology that is quite simple in the form of pots, stoves and natural local ingredients. For supporting activities in terms of procurement, local traders conduct operations that are carried out independently based on their capital. Moreover, the procurement of coloring is provided from locally harvested plants.

Table 4. Weaving Support Activities

| Inbound Logistics | Operation/Process | Outbo u nd Logistics | Marketing, Sales and Services |

| Infrastructure | |||

| The facilities passed or accessibility to the location of the farmers are quite good | The weaving location is done at home | The facilities passed or accessibility to the location of the farmers are quite good | In general, there is no supporting activity |

| Human Resources | |||

| Expertise in driving a motorized vehicle | The ability of human resources to weave using looms that affect product quality | Expertise in driving a motorized vehicle | There are no specific specifications in marketing |

| Technological Development | |||

| The technology used is in the form of motorized vehicles | The technology used is a loom instead of a machine | The technology used is in the form of motorized vehicles | There is no technology used |

| Procurement | |||

| Yarn purchases are done individually | Procurement of weaving equipment from own purchases and government assistance | In general, operations are carried out at their own expense | In general, there are no specific activities to support the main activities |

| Procurement of yarn is also sometimes done | |||

Weavers or craftsmen are supported by fairly decent road access in the form of paved roads to buy goods from local traders. In addition, weavers are also supported by their own homes as a place to weave threads purchased from traders to be used as products in the form of clothing or sarongs. In terms of human resources for internal logistics, weavers are supported by their expertise in using motorized vehicles so as to facilitate the collection of threads from local traders while the farmers operations are supported by knowledge gained from the experiences of their parents or they are simply self-taught.

For technological development, weavers are supported by ownership of motorized vehicles in the collection of goods from local traders. In addition, the weaving process is supported by simple technologies in the form of unmechanized looms purchased from loom makers and also supported by local government assistance. Moreover, in terms of procurement for logistics, weavers are supported by silk clothing stores. In a sense, the yarn obtained by weavers is not only from purchases from local merchants, but also from silk clothing stores. This is due to the relationships between the silk clothing stores and the weavers. The bond is in the form of cooperation between the two entities. In addition, the technology used is also obtained from government assistance and buying from loom makers.

Table 5. Supporting activities of silk clothing stores

| Inbound Logistics | Operation/Process | Outbond Logistics | Marketing, Sales and Services |

| Infrastructure | |||

| Sales location in the building itself | Product sorting container | Use of storefront as storage area | Loose sales in your own shop |

| Follow the product at the exhibition | |||

| Human Resources | |||

| The ability of entrepreneurs to manage products from weavers | The ability of entrepreneurs to sort products and price valuations | The ability of entrepreneurs in communication | The ability of entrepreneurs to include products at the exhibition location |

| Technological Development | |||

| The technology used does not affect product quality | Technology in the form of labeling tools | The technology used in transportation is not very influential, because it is carried out by courier services | Communication and information technology plays a role in marketing |

| Procurement | |||

| Retrieval of products in weavers using motorized vehicles | Plastic packaging | Performed by transportation courier services | Exhibition materials or equipment |

For supporting activities in terms of infrastructure for internal logistics, silk clothing stores are supported by sales locations in their own buildings being used as a place to store goods that have been purchased from weavers. In addition, the operations carried out by the silk clothing stores is supported by cross-section containers in the form of storefronts to sort out items that have been purchased from the weavers, and also for the logistics. In terms of marketing, silk clothing stores conduct loose sales supported by their own buildings and also include products at local product exhibitions in the city of Makassar and in other cities.

In the human resource category, silk clothing stores have expertise in managing incoming products from weavers to classify products. In addition, silk clothing stores have the ability to judge items for price. In terms of outbound logistics and marketing, owners of silk clothing stores are supported by communication and information seeking capabilities such as information about exhibitions. While in the technology development category, silk clothing stores have the technology in the form of labeling tools to label prices for each product so that it has a clear price. In addition, in terms of logistics, shop owners do not use technology because they only use freight forwarding services or couriers to send their products to consumers. Whereas in terms of marketing, owners of silk clothing stores are supported by communication and information technology in the form of smartphones to communicate with consumers and search for information about exhibitions and silk market prices.

Procurement at the silk clothing store is supported by considerable capital to buy goods from weavers. In addition, the silk clothing store also provides plastic packaging to support the packaging process for its products. Meanwhile, in terms of marketing, shop owners only provide silk materials or equipment to be included in exhibitions in the form of clothes hangers and others.

3.4 Marketing margin

In this study, marketing margins are calculated as the difference between the selling price of silk at the farm level and the selling price of silk at the merchant level. To find out the marketing margin value of each marketing agent, testing is carried out using a cost margin analysis tool, namely by calculating the amount of marketing margins, costs and marketing benefits and the share obtained by farmers.Marketing margin is the price difference between two or more levels of the marketing chain, or between the price at the producer level and the retail price at the consumer level. Marketing margins only represent differences in prices paid by consumers at prices received by producers, but do not indicate the quantity of product marketing.

The analysis of marketing margins would reveal how efficient the pricing is in the local market, and gives an indication of the importance of transaction costs facing traders, farmers and middleman, helping to identify and solve gaps in reducing marketing costs (SIFSIA, 2011). Marketing margins are presented in Table 6.

Table 6. Marketing Margin

| Actors | Purchase Price (IDR) | Selling Price (IDR) | Marketing Margin (IDR) |

| Farmer | 200000 | 400000 | 200000 |

| Local Trader | 400000 | 500000 | 100000 |

| Weaver | 500000 | 600000 | 100000 |

| Silk Clothing Store | 600000 | 900000 | 300000 |

From the results obtained in this study, the largest marketing margin is found in the silk clothing store, which is IDR. 300,000, while the smallest marketing margin is found in local traders and weavers, namely IDR. 100,000. The marketing margin of farmers is able to obtain an increased value due to the purchase price of silkworm eggs obtained free of charge from the assistance of the UTPD for Natural Silk. Meanwhile, the local traders and weavers experienced a lower marketing margin due to the higher purchase price at the previous level, and furthermore, production costs are also low enough to affect the selling price of the product.

3.5 Profit Margin

Profit margins, or net margins, are gross margins or marketing margins subtracted by marketing costs. Marketing margins are calculated to determine the actor who gets the most profit. Profit margins are presented in Table 7.

Table 7. Profit Margin

| Actors | Purchase Price (IDR) | Selling Price (IDR) | Marketing Cost (IDR) | Profit Margin (IDR) |

| Farmer | 400000 | 200000 | 4000 | 196000 |

| Local Trader | 500000 | 400000 | 32000 | 68000 |

| Weaver | 600000 | 500000 | 14000 | 86000 |

| Silk Clothing Store | 900000 | 600000 | 112000 | 188000 |

From the results of these calculations it can be seen that the larger profit margin is found among the farmers, at approximately IDR. 196,000, while the smallest profit margin of IDR. 68,000.00 is found among local traders. The profit margin obtained by farmers is greater due to the absence of marketing activities by farmers, whereby farmers just wait for local traders to come to pick up goods that have been produced by the farmer. The profit margins obtained by local traders are smaller due to the low selling prices coupled with labor costs when trading in the local market. The factor causing lesser profitability among local traders is due to the increasing component of the cost of product sold, and other costs (Hafid, 2016). The existence of community forestry (social forestry) programs can help to improve community welfare, especially improving community livelihoods of farmers. However, the government needs to regulate the system of trade in social forestry products, particularly in silk commodity, therefore the efficient trading and fair distribution of benefits can be achieved for each marketing channel.

4. Conclusions

Based on the research that has been conducted, it can be concluded as follows:

- From the results of the study, it can be seen that the main actors in the silk business are farmers, local traders, weavers, and silk clothing stores. While the actors who support the main actors of the silk businesses are the local district agency (UTPD Natural Silk) and the Office of Industry.

- The main activities in the silk business are found among farmers, local traders, weavers and silk clothing stores. From these results it can be seen that farmers act as producers of coarse silk thread, local traders act as processors of coarse threads into fine threads, weavers act as processors of fine yarns into clothing products, and silk clothing stores act as shops selling silk clothing products.

The widest marketing margin is found in the silk clothing stores, which is IDR. 300,000, while the smallest marketing margin is found in local traders and weavers in the amount of IDR 100,000. The largest profit margin is found in farmers, which is IDR.196,000, while the smallest profit margin is found in local traders, which is IDR.68,000. Overall, this highlights that there are opportunities to enhance value and improve livelihoods in among forest farmers involved in social forestry schemes. This provides a unique opportunities to ensure that local farmers bargaining positions can continue to be further strengthened to create more vibrant rural livelihoods.

Download Citation

Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)BibTeX

- ACIAR. (2012). Membuat Rantai Nilai Lebih Berpihak Pada Kaum Miskin. Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (hal. 100). Australian: Australian Goverment.

- Hafid, I. (2016). The Effect of Margin Profit and Total Assets Towards Sustainable Growth Rate of the Distributor and trade Company. International Journal of Business Management 10 (4): 423-428.

- Harbi, J., Nurrochmat, D. R., & Kusharto, C. M. (2015). Analisis Kelayakan Usaha Persuteraan Alam, Diversifikasi dan Inovasi Produk di Kabupaten Wajo, Sulawesi Selatan. Bogor: Institut Pertanian Bogor.

- Hakim I., Setiasih, I., Murniatih, Asmanah W., Rachman E., dan Sri R. (2010). Social Forestry. Menuju Restorai Pembangunan Kehutanan Berkelanjutan. Pusat Penelitian dan Pengembangan Perubahan Iklim dan Kebijakan.

- Nuraeni, S. (2017). Gaps in the thread: Disease, production, and opportunity in the failing silk industry of South Sulawesi. Forest and Society, 1(2), 110-120. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.24259/fs.v1i2.1861

- Popoko, S. (2013). Pengaruh Biaya Pemasaran Terhadap Tingkat Pendapatan Petani Kopra di Kecamatan Tobelo Selatan Kabupaten Halmahera Utara. Jurnal UNIERA, 2.

- Porter, M. E. (1983). Competitive Advantage. New York: Free Press

- SIFSIA. (2011). Price and Market-Structure Analysis for Some Agricultural Commodities: Marketing Costs and Margins. Agricultural Economics Directorate of the Ministry of Agriculture, Sudan. http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/sifsia/docs/Marketing%20Cost%20Margin%20Final%20May%202011%20(2).pdf

- Sihar, N. F. (2008). Kriya Tekstil Tenunan Sutera Tradisional Gedongan Sulawesi Selatan, Studi Kasus: Kabupaten Wajo, Sulawesi Selatan. Bandung: Institut Teknologi Bandung.

- Widarsono, A. (2005). Analisis Stratejik Rantai Nilai: Suatu Pendekatan Manajemen Biaya. Bandung: BHMN

References

ACIAR. (2012). Membuat Rantai Nilai Lebih Berpihak Pada Kaum Miskin. Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (hal. 100). Australian: Australian Goverment.

Hafid, I. (2016). The Effect of Margin Profit and Total Assets Towards Sustainable Growth Rate of the Distributor and trade Company. International Journal of Business Management 10 (4): 423-428.

Harbi, J., Nurrochmat, D. R., & Kusharto, C. M. (2015). Analisis Kelayakan Usaha Persuteraan Alam, Diversifikasi dan Inovasi Produk di Kabupaten Wajo, Sulawesi Selatan. Bogor: Institut Pertanian Bogor.

Hakim I., Setiasih, I., Murniatih, Asmanah W., Rachman E., dan Sri R. (2010). Social Forestry. Menuju Restorai Pembangunan Kehutanan Berkelanjutan. Pusat Penelitian dan Pengembangan Perubahan Iklim dan Kebijakan.

Nuraeni, S. (2017). Gaps in the thread: Disease, production, and opportunity in the failing silk industry of South Sulawesi. Forest and Society, 1(2), 110-120. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.24259/fs.v1i2.1861

Popoko, S. (2013). Pengaruh Biaya Pemasaran Terhadap Tingkat Pendapatan Petani Kopra di Kecamatan Tobelo Selatan Kabupaten Halmahera Utara. Jurnal UNIERA, 2.

Porter, M. E. (1983). Competitive Advantage. New York: Free Press

SIFSIA. (2011). Price and Market-Structure Analysis for Some Agricultural Commodities: Marketing Costs and Margins. Agricultural Economics Directorate of the Ministry of Agriculture, Sudan. http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/sifsia/docs/Marketing%20Cost%20Margin%20Final%20May%202011%20(2).pdf

Sihar, N. F. (2008). Kriya Tekstil Tenunan Sutera Tradisional Gedongan Sulawesi Selatan, Studi Kasus: Kabupaten Wajo, Sulawesi Selatan. Bandung: Institut Teknologi Bandung.

Widarsono, A. (2005). Analisis Stratejik Rantai Nilai: Suatu Pendekatan Manajemen Biaya. Bandung: BHMN